The Passion of Mayor Pete

The failure of progressives to rally around the young candidate in 2020 continues to haunt some Americans as a historic missed opportunity.

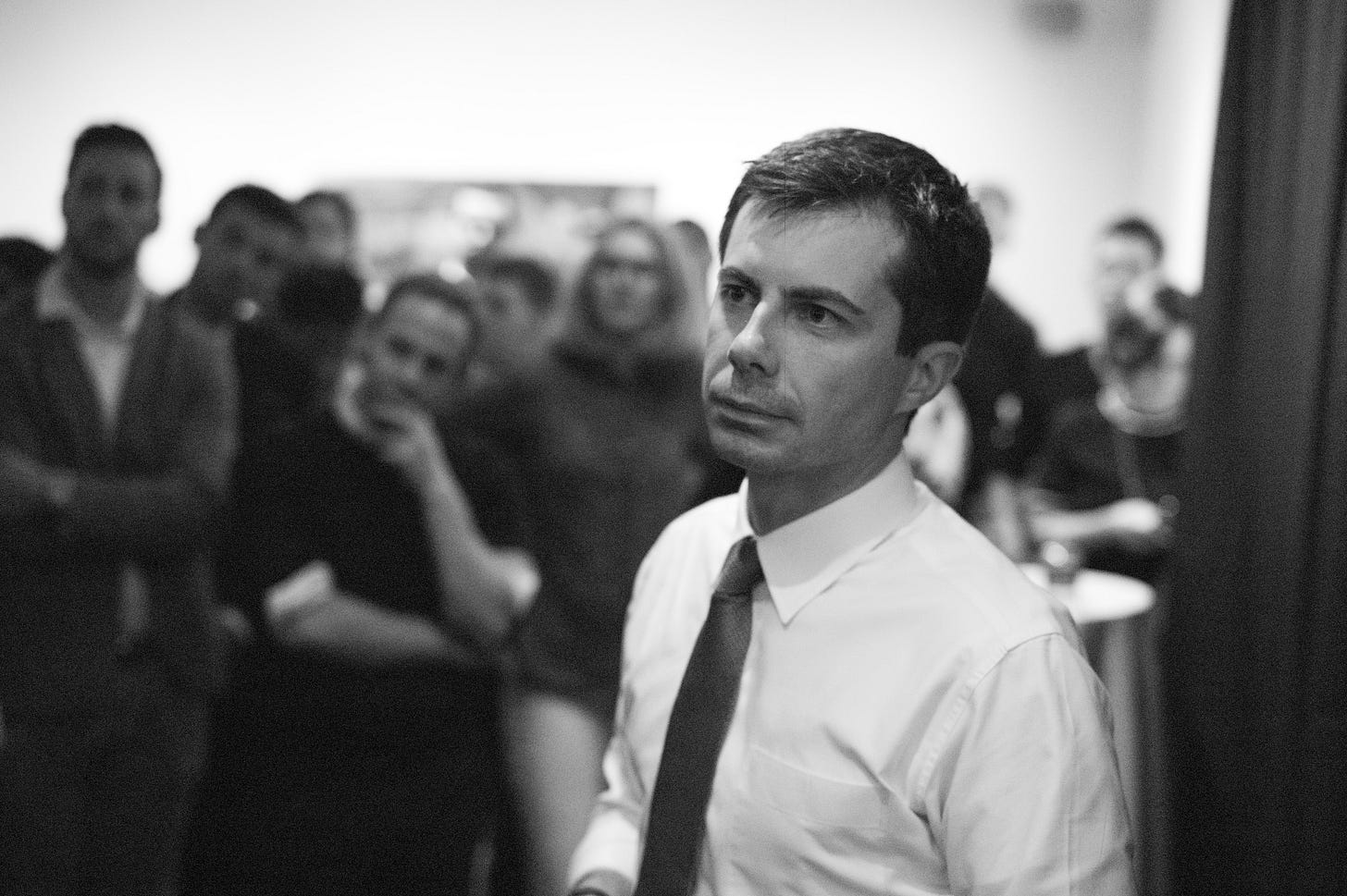

On a warm evening in 2019, the Brooklyn sky a fog of pink-gray as sunset neared, Pete Buttigieg stepped onto a stage in front of several hundred rapt supporters. It was June 28th, the Friday before World Pride Weekend—and 50 years to the day since the denizens of Manhattan’s Stonewall Inn decided that they’d had enough of the police raids and harassment, of the terror and discrimination they faced for being who they were, and erupted with a bout of riots that launched the modern gay-rights movement. Now, half a century later, Buttigieg had just become the first openly gay candidate to compete in a presidential debate, following a remarkable spring of surging in the polls. The atmosphere inside the concert hall was electric. The only time I’d witnessed as much civic joy was at Barack Obama’s inauguration, when a pall of reactionary ideology and cynicism lifted alongside the departing president’s helicopter and America seemed to affirm that truth and science—and one’s character rather than color—mattered.

Moments earlier, Annise Parker, the former mayor of Houston, had endorsed Buttigieg on behalf of the L.G.B.T.Q. Victory Fund. She praised the historic ground he was breaking, and “his love-based interpretation of scripture,” while arguing that he was America’s best presidential prospect for reasons having little to do with his identity. “He speaks with the openness and forthrightness and transparency that is sorely missing in American politics,” she said. “He is, in effect, the anti-Trump: experienced, accomplished, a veteran, patriotic, thoughtful. Everything we want.”

Buttigieg thanked Parker and the other L.G.B.T.Q. officials who had paved the way for him, then declared that his campaign was “for everybody who’s been told that they’re less than—everybody who’s been on the wrong side of an equation of belonging in this country.” But the movement would seek to build strategic coalitions, and to unite Americans around a positive vision, rather than rely on identity politics and grievance. “We have a choice about what identity is going to mean for us,” he told the crowd. “We’re not going to allow it to turn into You don’t know me! We’re going to insist that it’ll turn into I will stand up for you, whether you are like me or not.”

It had become disorienting, two-and-a-half years into the Trump presidency, to witness a potential President speak as Buttigieg did. To hear the truth plainly stated; decency embodied; the warnings of climate science respected instead of mocked. (He called on the country to “treat the next three, four, and five years according to their power to decide what the next 30, 40, and 50 are going to look like.”) The excitement in the crowd, that is to say, was tinged with heartbreak over the contrast between this leader and the status quo—roughly the difference between broccoli and arsenic. There was a palpable anxiety, at a moment of grave peril for our democracy and planet, about whether the country would wake to the promise of this campaign and realize that Buttigieg might just be the one best suited to answer the call of history.

Six months later, Buttigieg led the Iowa polls. The improbable was looking possible. “Moral courage speaks with a certain clarity. Listen for it,” Kevin Costner told a crowd in December, when endorsing the candidate in the state where his film “Field of Dreams” was set. “You've heard it throughout history. You know what it sounds like. We know who got it right, and what the echoes would sound like today.” It seemed possible that, as in 2007, the country had lit upon a young leader whose candidacy would have once been unfathomable, and who, partly for that reason, was uniquely suited to the moment. But a different narrative was emerging in certain quarters of the left.

That month, I was invited to attend a fundraiser for Buttigieg at the home of Kevin Ryan, the entrepreneur and founder of Business Insider. Ryan, who was named by the Observer as one of the 100 most influential New Yorkers of the past 25 years, has long supported progressive and humanitarian causes, and has served on the boards of Human Rights Watch, Mercy Corps, and Doctors Without Borders. Just before 6 P.M. on a dark, frosty evening, about 80 people arrived at his Upper West Side townhouse, entering and checking their coats at the lower-level entrance. Ryan greeted guests in his living room upstairs; a beautiful array of hors d'oeuvres was laid out in the kitchen. After Buttigieg arrived and posed for photos with donors in front of the Christmas tree, he stood on the stairs and began to speak, his voice booming. Scarcely 30 seconds had passed before there was a loud commotion downstairs. A protester, an apparent supporter of Bernie Sanders, had entered the home and was demanding to be let upstairs, claiming to be outraged that the press was not allowed into Buttigieg’s fundraisers. “He’s running as a midwesterner, but he spends all his time in rich people’s homes in Manhattan!” he shouted. (In fact, a press reporter was in attendance, in accordance with the campaign’s recently adopted policy, and tweeted much of Buttigieg’s remarks verbatim.) Ryan rushed downstairs and confronted the man, then led him out the door before closing the security gate. (A Twitter user posted a video of the encounter, writing “That time I got thrown out of #WallStreetPete’s billionaire fundraiser.”)

Buttigieg had continued speaking through the disturbance. “Think about everything that we’ve been through that’s brought us to this point,” he said. “We are not going to be able to move forward as a nation unless we can unify.” He spoke about his aim to reach diverse swaths of Americans, to invite voters of faith “to consider a future where they need not look at the White House and wonder whatever happened to ‘I was hungry and you fed me; I was a stranger and you welcomed me.’ ”

Outside, more Sanders supporters had gathered, and they began to bang on metal pots while yelling “Where is Pete? Where is Pete?”

“By the way,” Buttieg said, his face lighting up with a smile, “one of the things you learn in deployment is dealing with distracting noises.” The room cheered.

When Buttigieg concluded his remarks and took questions, a Broadway performer named Jesse Nager raised his hand. “I’m black, obviously, and I think the narrative that he’s not getting the black vote is silly,” Nager told the crowd. “They just don’t know who he is yet. When he goes and talks in black communities, people fall in love with him.” Buttigieg took questions about national security, about economics, about how to knit the country back together. He spoke about bringing farmers into the effort to fight climate change, about the need for a National Popular Vote, and for Constitutional reform to overturn Citizens United.

Outside, the protesters kept banging their pots. “Where is Pete? Where is Pete?”

He called for raising taxes on the wealthiest, for a 21st century version of the Voting Rights Act, for insuring that all Americans had access to healthcare, in a way that avoided the politically toxic path of forcing them off private insurance.

“Where is Pete?” Clank, clank, clank...

“Remember, the president’s big theme is, ‘Tolerate the racial division, tolerate the chaos, and in return, I will give you growth somewhat slower than Obama did,’ ” Buttigieg said, describing Trump’s boasts about the economy as being “like the rooster who thinks he made the sun come up.”

After thanking the group and encouraging them to spread the word with friends and family, Buttigieg briefly mingled with supporters who had swarmed around him. I asked Kevin Ryan what he made of the candidate. Ryan had met Obama before the former president announced his candidacy, he said, and left with the sense that he had just met a future president. Buttigieg impressed him similarly. “These are the two people in the last 15 years, who I’ve walked out [after meeting] and thought, ‘You know what, I think this person is just supernaturally intelligent, and just has a nice way around him,’ ” Ryan told me. Buttigieg and Obama are “different people,” he said, “but they’re friendly, they’re nice, they’re cool under pressure. You can imagine him getting the call at 3 A.M., you can imagine him having super smart people around him—and Obama did, too. And that’s what we’re looking for.”

Ryan was dismayed that a political protest was taking place somewhere other than outside Trump Tower, that Sanders supporters were turning their ire on such a promising progressive candidate. “That’s how you can lose, you know,” he said.

When I checked Twitter later that night, #WallStreetPete had begun trending.

Soon thereafter, of course, despite Buttigieg’s winning the Iowa caucuses, Democratic voters consolidated behind Joe Biden, whom many considered the safest choice to defeat Trump. Yet the failure to nominate Buttigieg—and, consequently, his not being on the 2024 Democratic ticket, given that Harris already appears too far left to many Americans and needs a non-minority running mate, despite Buttigieg’s having correctly refused to adopt far-left policies that Harris embraced in 2019 that would have amounted to electoral suicide—continues to haunt many of his supporters as a historic missed opportunity. Rather than selecting the figure, in 2020, who was likely the most politically gifted, the most capable of galvanizing Americans of diverse ideology—and whose candidacy embodied both generational and transformative change—voters opted for a man whose age would prove disastrous for his prospects of a second term. As Buttigieg pointed out, every time a Democrat had won the presidency in the last 50 years it had been a nominee representing a new generation and a perspective from outside Washington. Buttigieg clearly met this criteria, even as he was dismissed as being too young, and portrayed by the far-left as “centrist” or in the pocket of fossil-fuel interests, when the heart of his campaign was based on a deeply progressive platform, with a vital focus on democratic reform.

Amid the national emergency of the Trump presidency, and the growing chaos caused by its war on truth, Buttigieg emitted a preternatural calm. He spoke, and listened, when it seemed that most others were shouting. He was dismissed as “Obama-lite,” yet displayed a capacity for directness that escaped Obama. Buttigieg argued for policies more progressive than Obama’s, in language that was, ironically, more able to appeal to conservatives. Obama complained meekly about Fox News, speaking only euphemistically about its dangerous toxicity; Buttigieg went on Fox News, called out the hateful ethno-nationalism of some of its pundits, and did town halls that received standing ovations. For the first time in my life, as someone who hails from a conservative background in North Carolina, I saw a candidate capable of countering the ways that the network was cynically misleading millions and poisoning our democracy. Elizabeth Warren had masterfully summed up the outlet in four words, as a “hate-for-profit racket,” and refused (for understandable reasons) to participate in its charade. But the skill and boldness of Buttigieg’s head-on approach called to mind a remark that the folk legend David Crosby had made, calling Buttigieg “the smartest man I've ever seen in politics... He's smarter than all the rest of them put together. He's brilliant, and he's honest, and he's dedicated, and he's brave.” In an era when corrupt interests wanted voters to be confused about the truth, and to fear the left as socialists, a young progressive who spoke the truth most eloquently, and who knew how to reach vast swaths of Americans, was a force to be reckoned with.

The epistemic crisis in which this country remains embroiled is a defining challenge of our time, and a danger to democracy—and Buttigieg was poised to counter the epistemic fragmentation better than anyone. For years, American democracy has needed a leader who can take on the propaganda and expose it as fundamentally unconservative and antithetical to American values. The young Sanders supporters who were busy spreading disinformation about Buttigieg on Twitter (and at his fundraisers and rallies) might, instead, have rallied behind his campaign, seeing him correctly as the champion for their values that he was, and thereby helped give rise to a nominee who was more progressive than Biden, more transformative, better positioned to lead this country for two terms in the prime of his life. But in a disquieting parallel to the right’s epistemic closure, the far-left’s echo-chamber perpetuated the impression that Buttigieg’s progressive platform was that of a “corporate shill” in the pocket of billionaires. (Billionaires comprised .0054% of Buttigieg’s donor base, and their contributions amounted to .16% of the funds raised, according to the campaign.) I had watched, with horror and heartbreak, to see relatives and friends follow Fox News all the way into Trumpism. It was almost as disturbing to see progressives, caught in their own ideological fever dreams, attacking this young leader for being something that he wasn’t.

The banging pots at that December fundraiser were, for me, the sonic embodiment of our epistemic crisis. The distrust between, and within, our parties had metastasized; it had become a challenge to go through our days without the chaos overwhelming our senses and leaving us numb. Such is common in authoritarian societies, where citizens often grow resigned and apathetic, not knowing whom to trust, feeling that the truth is unknowable. Mayor Pete was uniquely equipped to counter this nihilism. His calm, soft-spoken demeanor masked a fierce intelligence, a keen awareness of the undercurrents of fear and confusion coursing through our politics, and a capacity to respond in a way that welcomed into the fight for democracy increasing numbers of, as he put it, “future former Republicans.” He displayed an unrivaled ability to speak to all Americans, to help us unite around values we share, and around truth itself.

On the night Buttigieg ended his candidacy, Peter Sagal, the National Public Radio host, joined those who were standing up, if belatedly, to the attacks on him, writing, on Twitter, “All the people On Here and elsewhere who insulted him, mocked him, for not being Democratic enough, for not being gay enough, for not being progressive enough, for being insincere and manufactured... you were all, every one of you, dead wrong the whole time.” William Saletan, of Slate, explained that the left’s critique of Buttigieg had been backward: “By sending signals of inclusion to moderates and disaffected Republicans, he made us comfortable with a candidate whose ideas were often well to our left,” he wrote. “I didn’t agree with him that the filibuster should be abolished or that justices should be added to the Supreme Court. But because those ideas were coming from him, I was willing to listen to them.” One of his supporters, a woman in her fifties named Deborah Knox, who had been inspired to politically canvass for the first time in her life, wrote on Facebook: “I often see him as somehow putting his arms underneath everyone, speaking progressive with a conservative accent to those who can hear that better, picking everyone up and saying, 'Folks, we do need to move forward, but we are going to go together and I’ve got you!’ ”

As the current race marches on, and America continues to be afflicted by a party that has lost touch with its conservative values and turned away from democracy—having built an entire media ecosystem that keeps its audience addicted to the dopamine rush of resentment and tribal hatred—I keep thinking back to the giddiness in the concert hall five summers ago, when people from all over the world had descended on New York to mark the progress of half a century. As Buttigieg’s speech drew to a close, the applause built to a crescendo. “Will you help me bring about a new day in American politics?” he asked. “And as grim as this moment might be, will you help me find joy in that process?” The crowd roared, drunk at the thought of what might be possible.