Live From New York, It's Flo Fox

Flo Fox shot out of her apartment building and turned right. She was steering her motorized wheelchair with her left arm—the only limb she could move since multiple sclerosis set in at 30 and, over three ensuing decades, left her mostly paralyzed and scarcely able to see. Now, at 61, Fox was legally blind but inhaling the sunshine, navigating with what little vision remained, her purple hair flapping in the wind. Jack’s 99 Cent store, her favorite, was ten blocks away.

Around her neck hung a silver point-and-shoot Olympus. For nearly four decades, Fox hadn’t ventured outside without a camera. No longer able to take pictures—her left arm was too weak—Fox had begun delegating the task to her attendants. Today that was Marie, a friendly blond woman in her late 40s who worked for Fox four days a week, from early morning until seven p.m., when another helper arrived to spend the night. Marie had grown accustomed to lending her services to artistic ends.

Several times en route to Jack’s, Fox halted and, in her raspy voice, issued a photographic edict, advising Marie on how to frame a shot. The first time, Marie couldn’t see anything that looked remotely photogenic. Fox explained that the building she had in mind was being reflected through the windshield of a parked car. “Give the camera a hard-on,” she directed. Marie pressed zoom, sending the lens shooting out four inches, and snapped the shot.

“When I started working with Flo, I didn’t know anything about photography,” Marie said afterward. “What few people realize about her is that she is a teacher.”

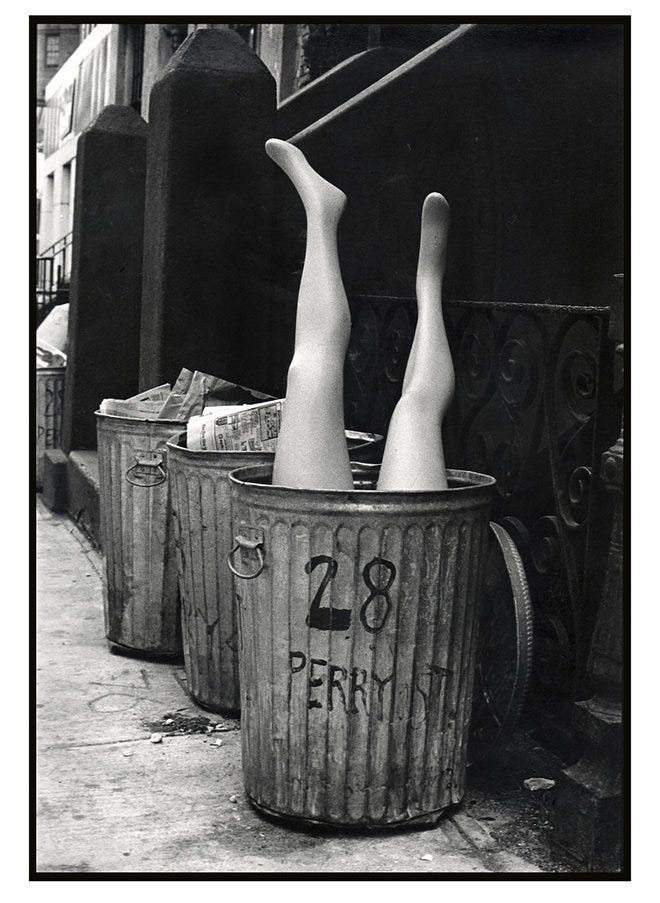

Fox sees herself chiefly as an artist. She’s shot pictures of the homeless, of workers building the World Trade Center in 1973, of cemeteries throughout America and Europe, of Halloween parades. She once rented a helicopter to photograph the Flatiron Building. Some of her photos, such as one of an old man talking to his dog, have been sold as postcards.

Fox was now living at Selis Manor, a community center in Chelsea that specializes in services for the blind. Her one-bedroom apartment was flooded with stacks of pictures; a few dressers and several cabinets contained, she estimated, another 85,000 photographs, the results of what she knew from an early age would be her life’s work. “Photography is my existence,” she said. “It keeps me going.”

Inside Jack’s 99 Cent store, Fox asked to see various trinkets on the shelves. Someone took down a small plastic Jack-O-Lantern. “Bring it closer,” she said, straining her left eye. “Cloooserrrr”—until the object was inches away. “How would it look next to a you-know-what?”

Fox was searching for something to photograph with a penis. The project she was most proud of, the 69-page “Dicthology,” incorporates lots of such paraphernalia. One page features a baby alligator with the tip of a phallus emerging from its mouth. The idea arose, she said, in an art director’s office in the late 70s, where she saw the little stuffed reptile with an open mouth: “So I said to him, ‘Wouldn’t it look great if you put your dick through it and it made a tongue?’” (The picture is titled “See Ya Later.”)

“Dicthology” features pictures of penises dressed as, among other things, a hot dog, a mouse trap, and Joe Camel, in photos that are both crude and playful. “Monumental Erections” features an erect penis superimposed beside the Empire State Building; “Beau-quet” involves a floral arrangement.

“I’ve photographed the penis of every man who has been in my apartment in the last twenty years,” she told me. “Except yours. Do you wanna be in my Dicthology?”

Fox was born and raised in Miami. Her father died when she was two. Six months shy of graduating ninth grade, she asked her mother for a camera. It mattered little that she’d been born blind in one eye and had poor vision in the other; she knew she would need one. Her mother promised she’d get one the day she graduated. But a month later her mother died, of cancer. Fox’s oldest sister and her husband, who were both 20, moved in to care for their siblings. During the months leading up to her ninth grade graduation, Fox recounted impassively, her brother-in-law repeatedly came into her room at night and molested her. On the day she graduated, she received a children’s camera, all her sister could afford. She gave it to a friend, and the next day she ran away.

By 18, Fox had married and was living in New York. A few years later, after giving birth to a son, she left her husband and began working as a costume-maker. With her first paycheck as a single woman, she bought a Minolta. “I said, 'Now it’s my turn. Now everything’s for Flo.'” She began taking the camera wherever she went. Photography became a means not only of expression but of self-preservation: “I won’t remember anything unless I’ve taken a picture of it,” she said.

One day in 2004, Fox's niece paid her a visit, and lamented to her that her life had gone off the rails. She told Fox goodbye, then went to the roof of the 12-story building and jumped to her death. Fox made local news when she emerged from the building with a camera. “She too had been abused,” Fox told me. Photographing the tragedy was natural for her, she said; she could never divert her eyes, nor her lens, from the streets.

As Fox recounted the events, Marie was feeding her chicken and rice from a styrofoam container. Fox’s skin was pale, her features symmetrical. She was skinny, and retained some of the beauty of her youth: a small and straight nose, a pronounced jaw, soft cheeks. Her hair was thin and, where not dyed purple, dark.

When she finished eating, Marie pressed a button and the wheelchair began to recline. Fox was explaining the idea behind a magazine spread she took, eleven artsy photographs of herself that Playboy published in 1976. “Originally, my fantasy was an older woman walking down a cobblestone street with lots of groceries, and her bag was tearing… And as the bag tore,”—she paused to tell Marie to stop the recline—

oranges fell all over out of her bag, onto the cobblestone, and as she reached over to pick it up, and her skirt raised up in the back, she saw a young guy walking down the block, who then offered to help her carry home her groceries. So the fantasy was…an older woman and a young stud.

Fox beamed and gestured toward me. “Ha!”

In her late 30s, as her body was faltering, Fox began to realize the challenges the disabled faced in navigating Manhattan, and took to carrying concrete and a trowel to create curb-ramps where needed. She also occasionally planted herself in front of city buses that lacked lifts. “The driver would call the police, and I would say to someone, ‘Grab my camera! Photograph these police arresting me!’ And people would photograph me and not run away with my camera.”

Gigi Stoll, a fashion-model-turned-photographer, called Fox her first photography mentor. They met in 1990 after Stoll encountered one of Fox’s books, “69 Photographs by Flo Fox,” containing pictures from Manhattan’s streets. She fell in love with Fox’s work and reached out to her, and they became friends.

“It’s unfortunate she doesn’t have the recognition she deserves,” Stoll told me. “She’ll probably have to pass before she’s appreciated.”

Stoll described Fox as a modern Weegee, the famous New York photographer of the 1940s and 50s who turned his camera on crowds of spectators to see their reaction to fires, crime scenes, and so on. Much of Fox’s work, in fact, focuses on the unglamorous—ordinary citizens, ads posted on phone booths, the homeless. In the local society of New York photographers, “they hold [Fox] in very high regard,” Stoll said. “She’s respected in that group. In the fashion world, no one has heard of her.”

Ten years ago, Fox was diagnosed with lung cancer and underwent radiation, which shrunk the tumor near her left clavicle. She now sees her doctor every four months, but so far the cancer has remained dormant. (Her medical bills amount to about $150,000 annually. Medicaid and Social Security cover her expenses.) During my visits with her, it was impossible not to be struck by her spirit and humor. Not once did she seem sad for herself. I asked if she suffered or worried about her health. “Some people in my condition either suffer or are numb,” she said. “I’m numb.”

If there was pressure in her life, it was the need that she felt to create a legacy, to ensure that her work didn't die with her. She may have been helped in that respect by the late comedian Joan Rivers, who paid Fox a visit a few years ago. Fox ended up in Rivers’s 2010 documentary, “A Piece of Work.” (A Youtube video of the moment is here.) Rivers is later shown becoming emotional while watching an interview of Fox from the early 1980s, before she lost control of her limbs.

"There's a sexy, young, artistic, edgy, New-York-tough, bohemian girl," Rivers says. "Life is so mean."

In the gritty black-and-white of Fox's photography, much of that meanness comes through. But there's an energy pulsing through her work, a vibrancy that finds something in the darkness beyond pain—something beautiful, something playful, something funny. Her archives contain a universe of images of New York: its architecture, its people, its layers of sexuality and suffering and accidental fate. They resound with an unbridled passion for life.